Selecting and sharing books for children can be a challenging exercise as we try to ensure a balance of views and perspectives that is also shaped by own experiences and preferences. Lyndon Riggall provides food for thought as he raises some of these issues to consider the importance of incorporating contemporary children’s literature into the mix.

While it is always exciting to see children’s books making national headlines, it can be concerning when it isn’t necessarily for all the right reasons. Consider David Koch, two weeks ago on Sunrise, announcing to a guest, “You’ve made me feel guilty… I give all of the grandkids a copy of Possum Magic on their first birthday—I’m now a bad grandfather!”

What Koch is responding to is a study conducted by Edith Cowan University’s Helen Adam and Laurie J. Harper, in which they visited Australian and American schools and looked at the most popular books being read to children. It will be of no surprise to readers of this blog that these collections of most-loved texts often included books like The Rainbow Fish, The Cat in the Hat, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, and Rosie’s Walk… beloved classics from the last century which have stood the test of time and whose popularity has endured for good reason. The researchers had two points of contention with the overall landscape of the books currently being shared in modern classrooms: firstly, that they very rarely represented humans at all, and secondly, when they did, it was often a limited portrait of society that lacked cultural diversity and which reinforced stereotypes of gender and failed to reflect a spectrum of abilities.

A few highlights from the data included that the books surveyed reinforced traditional gender constructs and roles 85% of the time, and that across the schools they visited there was never any expression of trans or non-binary characters. While schools in the United States were a little more successful in offering multicultural narratives, it was noted that most of these texts were in storage and brought out primarily for special occasions or to bring further attention to cultural festivals or events. According to Dr Adam, around 25% of Australian children would “very rarely see someone like them or their family represented in a book.”

David Koch, of course, is not a bad grandfather for buying his loved ones a copy of Possum Magic, an indisputably masterful picture book. The classics are classics for a reason: they resonate with readers and they offer opportunities for connection across the generations. Teachers, parents—and for that matter most of us when given the opportunity—will reach for what we know, and, more importantly, what we know works. The reason that censorship of such beloved writers as Dr Seuss and Enid Blyton is so offensive to so many is not about the appropriateness of the text itself (which often, to be honest, could often use a little airbrushing), it is the fact that someone is tampering with an experience that has been so central to our own journey, and a journey that we feel has done us no harm. Teaching texts in context and questioning them is a key part of the solution to this, but the latest criticisms run deeper. These kinds of studies don’t merely challenge individual texts and writers, they question the wider morass of literature and what we have traditionally regarded as good reading for young people.

Let me state, categorically, that it is my feeling that we have a more important battle to prioritise here, which is not what books children read, but more crucially the question of whether or not they actually read at all. A child reading The Cat in the Hat or The Very Hungry Caterpillar should not be said to be making a mistake when the very act of reading itself is—I believe—an inherent good in almost every circumstance. Nostalgia is a potent and sometimes dangerous influence on our choices, but I also have to be careful of my own hypocrisy... I bought my goddaughter a copy of Possum Magic before she was even born, and I am not quite so foolish as to publish a blog claiming that we all need to move on to reading only diverse contemporary texts while my Goodreads page is quietly announcing that at the same time I'm halfway through a re-read of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.

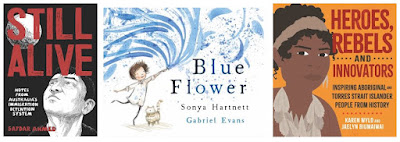

The kinds of accusations made by this study are, of course, reflective of why the CBCA even exists in the first place. Looking at this year’s shortlist, it is obvious that a classroom with the wisdom to select these texts for sharing with its students would dodge many of the criticisms levelled by Adam and Harper in their study. Across their totality, both picture books and novels in this year’s awards—subtly and overtly—explore experiences of immigration, Australia’s First Nations community and living with a diverse gender and sexual identities. Put simply, if parents and teachers don’t know where to start when it comes to broadening their school’s selection of literature, this is one answer to how it might be easily done.

A few years ago I attended a panel on “intersectional” literature—that is, narratives that explore multiple angles of diversity. A panellist asked all of us, “When did you first see someone you recognised as being like you in a story?” For me, it was almost immediately upon being able to read. For others, it took much longer. For an even smaller group of people it has never happened. My latest children’s book is about a magpie and a kookaburra… animal characters abounding. I love the classics, and I certainly share them with the young people in my life, but I also agree completely with the findings of Adam and Harper’s study. Life, teaching and our book collections are all about balance, and offering children diverse stories has two wonderful outcomes: it shows the broader community of children the reality and value of these stories, and it allows those who will recognise their own lives in those narratives to feel seen.

Any child’s library should have a selection of books that the people who care about them love and want to share with them, a selection of books that are fun and foolish (with perhaps even a few non-humans thrown in), and a selection of modern stories that challenge their perception of understanding of the world around them and encourage them to grow in their recognition of others. We owe it our children to keep bringing these new stories into the limelight…

After all, that’s how we make the classics of tomorrow.

Reference

Adam, H., & Harper, L.J. (2021) Gender equity in early childhood picture books. A cross-cultural study of frequently read books in early childhood classrooms in Australian and the United States. The Australian Educational Researcher, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13384-021-00494-0

Lyndon Riggall is a writer and teacher living in Launceston. Along with illustrator Graeme Whittle, he is the author of the picture book Becoming Ellie, and can be found at http://www.lyndonriggall.com. Lyndon’s latest book, Tamar the Thief, was written for the Tamar Valley Writers Festival and released for free on their website. It can be found at https://www.tamarvalleywritersfestival.com.au/storytelling/

No comments:

Post a Comment