Readers who could not attend the CBCA Conference in person, or as a virtual participant are in for a treat with the first of several posts that bring great moments to life. This week, Lian Tanner, shares some perspectives as both an ‘on the ground’ presenter and a participant.

On the weekend of June 10/11, in the depths of a very cold Canberra winter, teachers, librarians, writers and illustrators gathered together for the 14th National Conference of the CBCA. The theme was ‘Dreaming with eyes open…’

There were many highlights, including the Saturday night dinner where Jackie French and Bruce Whatley spoke about the writing and illustrating of Diary of a Wombat (which is being honoured with an Australian Mint coin to mark its 20th anniversary), and Margaret Wild was presented with the third CBCA Lifetime Achievement Award.

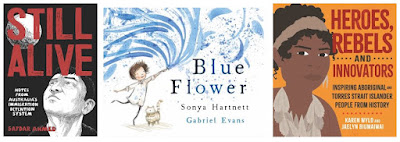

One of my personal highlights was the Friday night BookFest. A bit like speed dating, it showcased the work of 21 authors, who had three minutes each to present their latest book in a way that would excite and entertain the conference delegates. It was a great format, fast moving and fun, with a drum roll between each author.

Another favourite was listening to illustrators Dub Leffler, Bruce Whatley and Tania McCartney talking about their work, showing examples of how they work, and discussing the highs and lows of illustrator life.

And then there was the hilarity of Stephanie Owen Reeder, Sami Bayly, Claire Saxby, Gina Newton and Nicole Gill sharing stories about why they write and/or illustrate non-fiction books about animals, how they got into the field, and their unlikely adventures in the pursuit of their craft.

... The Great Debate: Fantasy vs Reality

But many would agree that THE highlight (or at least the funniest part of the weekend) was Sunday's Great Debate, a battle over which was better: fantasy or reality. The brief given to the debaters? To be entertaining. (And no bloodshed.)

|

| © The Great Debaters - 2022 CBCA Conference |

Moderator Deborah Abela introduced the debate with humour and razzmatazz. Then it was on.

I was up first, for Team Fantasy. I began with the complaint that Team Reality had been allowed to bring in as many props and visual aids as they wanted – chairs, tables, bits of paper. Even microphones! All we’d asked for was one measly orc, and it wasn't allowed.

I pointed out – in between jokes – that fantasy teaches kids that they can change the world. And that it can illuminate and reflect real-world problems. Because the very best sort of fantasy is about the things we care about; friendship, struggle, love, courage, hope.

Sue Whiting was next, for Team Reality. She spoke with passion about the fact that realistic fiction shows us what humans are made of, and that there is some powerful magic right there.

She also pointed out that it celebrates all kinds of backgrounds and races and families, a representation that is long overdue. To my dismay, I found myself nodding agreement as she spoke.

Then Kate Temple, for Team Fantasy, stripped the magic from well-known novels to show how hollow they would be without it. Her examples were all hilarious, but my favourites were probably Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone and Alice in Wonderland.

The former, with the magic removed, became 'an orphan boy in foster care goes to boarding school and finds he is quite good at hockey'. Alice became 'a girl falls asleep on a river bank. Later, she wakes up.'

The final speaker was Pip Harry, a last minute substitute who nevertheless did Team Reality proud as she pointed out the magic in everyday life: cicadas emerging from their shells, the moon, laughter, the ocean, music, art, the connection between friends.

There were two unexpected visitors at the end of the debate. Gandalf arrived to support Team Fantasy – a masterstroke, we thought. But then Oliver Twist came creeping up to the podium to ask for more, on behalf of Team Reality.

It was an hour of creativity and laughter, with a great reception from the audience. Their eventual vote was evenly split, at which Sue Whiting pointed out that books were the real winner!

|

Lian Tanner

Author

http://liantanner.com

https://www.facebook.com/liantannerauthor

Instagram: liantannerbooks

Editor’s note: I agree 100% - the debate was a winner - a riveted audience joining in the hilarity. And yes, books may have been the overall winners but personally, I think that fantasy won on the day!