Looking for inspiration? It is a pleasure to welcome back Michelle Davies, librarian at The Hutchins School, with new ideas and strategies to engage middle school students in reading for pleasure.

Middle school can be a tricky time. Students are growing, changing, and often navigating a whirlwind of emotions and interests. During all that, how do we get them excited about reading? It’s not only possible it can be fun! Here’s how we work to engage middle schoolers in reading for pleasure.

Structured Wide Reading Sessions

We have found success in engagement follows a clear, engaging routine to maximise student interest and reading exploration. Typically, our program is structured as follows:

An interactive activity that connects students with books and sparks curiosity. Such as “Mystery Book”

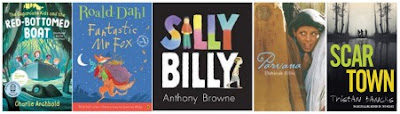

This fun guessing activity gets students listening closely and thinking critically. Five book covers are displayed on a digital screen, all from the same genre, each numbered one through five. The librarian holds up a physical copy of one of the books but keeps the cover hidden. Then, they read a chapter or short excerpt aloud. As students listen, they try to match the chapter to one of the covers. When the reading ends, each student writes down the number of the book they think it came from. Once all guesses are in, the librarian reveals the correct book. Students who guessed correctly go into a draw to win a sticker for their laptop or water bottle.

It’s simple, engaging, and a great way to introduce new books while building listening and inferencing skills whilst wrapped in a little mystery and fun.

Or a character exploration exercise such as “Whose Shoes are these?”

This begins with a read-aloud of a carefully chosen book excerpt, one that introduces a character both physically and emotionally. After a brief discussion, students talk about how the character looks, feels, and what the text reveals about them.

Next, in pairs, students are each given a picture of a different pair of shoes, glittery boots, hiking boots, colourful sneakers. From their shoes, they create a character: Who might wear them? Physical appearance How do they feel? Where are they going? Students then share their characters and imagined settings with the group. It’s a fun, creative way to connect physical detail to emotional depth and bring characters to life.

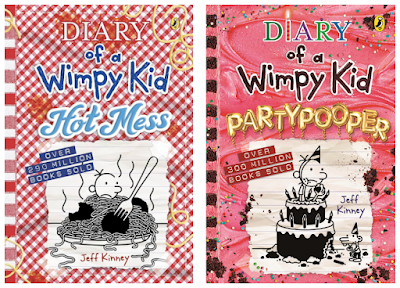

Next, New and recommended books are promoted to keep the reading options fresh and exciting. This could be a book talk, a promotion of new titles, focus on a particular genre, or student-led recommendations. The goal is to introduce books that align with students’ interests and encourage them to pick up something new.

After that, students move into silent independent reading time. This quiet reading period allows them to dive into their chosen books, practice fluency, and build reading stamina. Providing this dedicated time in the schedule shows students that reading is a valued and enjoyable activity.

Finally, students log their reading progress on Beanstack, a digital platform that uses gamification to boost engagement and reward effort with badges and challenges. Readers can check their progress on the challenges and strive for the next award, building a sense of momentum and motivation. We also run a leaderboard competition between classes, where the class with the most reading logs at the end of the term wins a pizza lunch. It’s great to see the excitement build as students track their class’s standing and encourage each other to keep reading. The platform also gives us valuable insights into reading habits, preferences, and progress.

Insights and Observations

We have found that middle schoolers still love being read aloud to, especially when it’s an engaging story with a dramatic narrator.

They enjoy stories that reflect their own experiences. Books that feature relatable characters, real-life issues, and strong emotional journeys enabling them to see themselves and the world more clearly.

Choice is powerful. When students are allowed to choose their own books, they’re far more likely to read. We create opportunities for student-led book selection and encourage them to explore different genres until they find what clicks.

There’s nothing more rewarding than creating space for choice, connection, and celebration, and witnessing the impact as students walk through the door with books in hand.

Michelle Davies

Librarian (Middle/Senior School)

The Hutchins School

Editor’s note: Take the time to search for 'teaching strategies' on the blog (top left search box) for a range of literature inspired ideas from Michelle and other contributors.