Children’s Publishing and Artificial Intelligence

by Lyndon Riggall

You could be forgiven for thinking that we were living in an episode of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror or a Ray Bradbury short story. The product is called Oscar, a mobile application in which, with a few button presses (selecting characters, story details, and even a moral message), a bespoke bedtime story is generated by an artificial intelligence, tailored to your requests and/or your child’s specific interests. It’ll even throw in the illustrations. You can paint me surprised that when the AI revolution came, it came for the creatives just as quickly as it came for everyone else. I can remember at school being comforted by my careers counsellors that my ambition to be a writer put me in a field that was lovingly cocooned from threats of automation. I suspect now that some of those flow charts have had to be updated. Goodnight sweet princes and princesses, may flights of coding sing you to your rest.

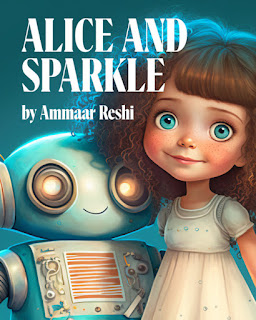

Alice and Sparkle, 2022,

created by Ammaar Reshi

It didn’t take long to bring us here. Within weeks of widespread access to artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT and art creator MidJourney, the designer Ammaar Reshi published the first AI-generated picture book, called Alice and Sparkle (fittingly, about a girl who becomes friends with a robot), which was created entirely by prompts fed into online tools. The work had understandable and predictable flaws (pedestrian sentences, clichés, odd illustrations with claw-like hands, inconsistency of lighting and shadow and weird objects floating the background) but it was also, inarguably, a children’s book of comparable quality to many that get published. What does it mean that a picture book can now be created with almost no human input whatsoever?

The first quagmire we find ourselves traversing is that of copyright. For the time being, perhaps, the most useful precedent is that of the “monkey selfie,” in which British wildlife photographer David Slater had his camera operated by a curious Celebes-crested macaque, which then took several photos of itself. While hotly contested to this day, it has been the general legal understanding that no-one owns these photos. They were taken with Slater’s equipment, but he is not the photographer, and a non-human cannot be said to hold copyright for an artistic work. Artificial Intelligence outputs are usually considered to follow the same logic, but it’s also more complicated than that. The San Francisco Ballet’s Instagram page became a hot-bed of anger late last year when the company used generated images to produce promotional pictures for their performance of The Nutcracker. Many in the comments argued that these (admittedly captivating) outputs could only be generated because of the hard work of other artists who provided the models for them without recompense or permission, meaning that while nothing may be recognisable from their own work and style, those who generate them could be argued to be exploiting the artworks of the past while simultaneously robbing artists of future work.

From a teaching and writing perspective, my own relationship with artificial intelligence can be summed-up in two words: cautious and curious. I use Artificial Intelligence almost daily, for all sorts of things, not the least of which are myriad simple tasks for which basic, bland documentation needs to be filled in, or for my own pleasure and fascination in seeing what the technology’s strengths, flaws and limits are. When it comes to creative writing, my personal ethos is very similar to the one that I espouse in the classroom. I talk to my students about the idea of “entitlement,” and the concept that so many people these days think you should be able to have something without working for it. A writer who uses Artificial Intelligence to produce their work will create, at the very least, a story or essay that is often of comparable quality to others, and sometimes better (most of what I see coming out of ChatGPT from my own experiments I would assess at a “B” standard in Years 11 and 12). But what does it mean to have that assessed? What does it mean to get good marks? To be proud of it? Legally, an output by an AI is said to have been created by no-one at all. Artistically, I think I would argue the same. Artificial Intelligence can delight, inspire and challenge. It can create, and to a degree even collaborate. Yet I would argue that its outputs are not, in any way, the work of the human author who inputted them. I guess the real question here is whether you want to write a book, or whether you are happy simply to have written one. Does the process mean something in and of itself?

While it is fascinating to be able to insert details of your child into a machine to create a tailor-made bedtime story for them, or to whip up a complete picture book in a weekend, I doubt we’ll be finding anything like the outputs of Oscar or Alice and Sparkle on the CBCA shortlist any time soon. The tech is inarguably impressive, but the vast majority of what it does comes down to predicting the next word in a sequence based on all of the words and requests that have come before it. AI can create pretty much anything, just as long as what you are looking for is the prototypical example of it.

We live in exciting, changing times. Nevertheless, I hope that tonight, if you are lucky enough to tuck in a little person and to read them a story, you will keep your iPad well away. Artificial Intelligences can give us what we ask for. For now, I think it is still with other humans where we find what we need.

Lyndon Riggall is an English teacher at Launceston College, the author of the children’s picture books Becoming Ellie and Tamar the Thief, and Co-President of the Tamar Valley Writers Festival. You can find him online @lyndonriggall and at www.lyndonriggall.com.

Editor's Note: Food for thought! You can delve deeper into coverage on Ammaar Reshi and his AI publishing in this article (Popli, N., 2022, December 14, Time.) and the Monkey selfie copyright dispute. (Wikipedia contributors. (2023, March 30). Monkey selfie copyright dispute. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 29, 2023)

No comments:

Post a Comment